16 Review

Acknowlegments

NotebookLM, Perplexity and Google were used for collecting and summarizing references while preparing these lecture notes.

Overview

- This week we will be reviewing 2 recent papers the cover the topics we have been learning about this term.

- Each of you will have the opportunity to select, review and share a paper with the class next week.

- We will also review some sample exam questions (see slides for these questions).

Papers

Genomics for a Better Reference

Logsdon et al. (2025) details the sequencing and analysis of 65 diverse human genomes to improve the understanding of human genetic diversity and enhance genomic reference resources.

Background required to understand the paper

- Diverse sets of complete human genomes are required

- Construct a robust pangenome reference

- Characterize complex structural variation (SV)

- Long-Read Sequencing technologies

- Generate the first complete human genome sequence

- Required for highly contiguous diploid assemblies

- Significantly increases sensitivity for detecting SVs (variants >50 bp in length)

- Phasing

- Long-read data is coupled with phasing data

- Hi-C, Strand-seq or trio data to assemble both haplotypes accurately

- Previous Gaps

- Gaps continue to persist genome assemblies

- Genetically complex loci are especially difficult to close

- Examples: centromeres, MHC, highly repetitive regions

Phasing with trios

- Parent-child trios are sequenced

- Enough genetic diversity exists between parents that haplotypes in the child are unambiguous

Phasing with Hi-C

- DNA is cross-linked with formaldehyde

- Links are created between DNA that is nearby in 3D space but potentially far appart in the 2D sequence

- When DNA is fragmented, chimeric reads are created

- Paired-end chimeric reads are aligned to the linear genome

- Read pairs that originate from distant locations are inferred to be from the same haplotype

Strand-seq

- mRNA is transcribed from a single DNA molecule

- Complete mRNA strands are mapped back to the DNA to determine haplotypes

What fundamental questions does the paper address?

The paper addresses how to create a comprehensive and diverse genomic resource to resolve the most challenging regions of the human genome and utilize this resource to improve variant detection

What is the full extent of complex structural variation across diverse human populations?

Can near-complete, phased assemblies of diverse genomes be achieved, closing gaps, particularly at centromeres and complex segmental duplications (SDs)?

Can complex, medically relevant loci (e.g. MHC/HLA) be sequenced to complete continuity?

Can these highly contiguous assemblies improve genotyping accuracy and the detection of rare SVs from standard short-read data?

Study design

Aim: produce a genetically diverse sampling of nearly gapless chromosomes

Haplotype Assembly: 130 haplotype-resolved assemblies were constructed from 65 diploid individuals

The approach combined the complementary strengths of PacBio HiFi reads and ultra-long Oxford Nanopore reads

Additional multiomics data includes Strand-seq, Hi-C, RNA-seq, Iso-seq

- Pangenome Integration:

- Newly assembled genomes were combined with the draft pangenome reference

- Create a pangenome graph for subsequent genome inference and genotyping experiments

- Multiple variant callers were used, including: PAV, DipCall, SVIM-asm, SV-Pop

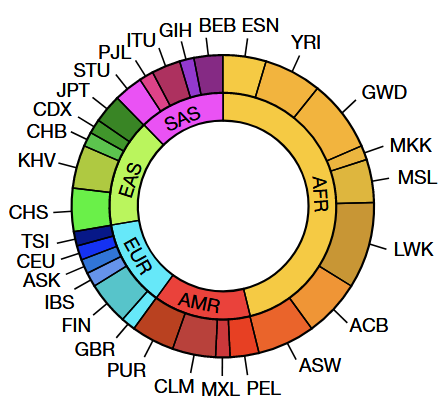

Sample collection

65 human lymphoblastoid cell lines were selected for sequencing

63 of 65 came from the 1000 Genomes Project (1kGP) cohort

- Additional two samples selected to add diversity

- African, American, East Asian, European, South Asian

- 28 population groups

- Maximize genetic and Y chromosome lineage diversity

Coverage:

- ~47-fold for PacBio HiFi

- ~56-fold for Oxford Nanopore (about 36-fold ultra-long)

Three family trios included for validation

12 individuals had long-read Iso-Seq data generated for functional analysis

Data analysis

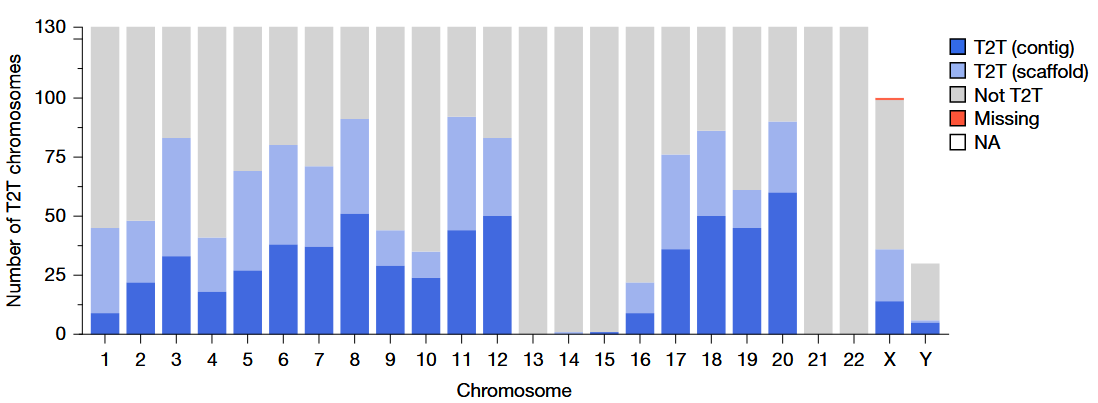

- 130 resulting haploid assemblies were

- Highly contiguous (median contig size of 137 Mb)

- Highly accurate (median base-pair quality value between 54 and 57)

- Estimated to be 99% complete for known single-copy genes

Assemblies closed 92% of previously reported gaps

602 chromosomes were assembled as a single gapless contig (telomere to telomere (T2T))

An additional 559 as a single scaffold

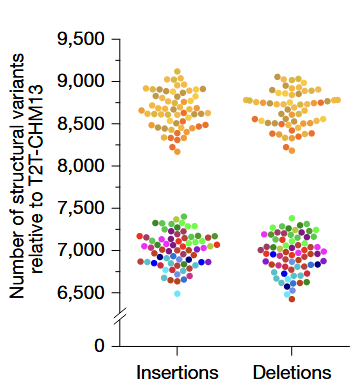

- Variant Discovery

- Phased assemblies identified 188,500 SVs, 6.3 million indels, and 23.9 million single-nucleotide variants

- Overall size of the SV callset increased by 59% compared to previous efforts

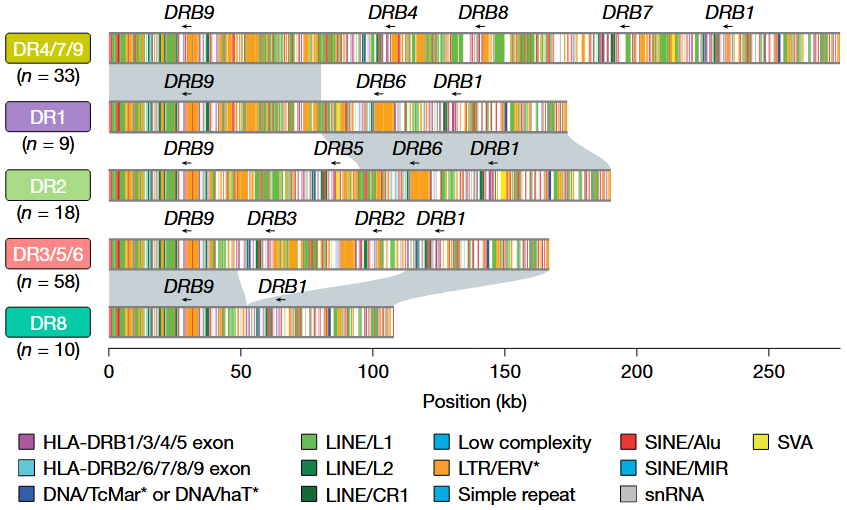

Segmental duplications

- Average of 168.1 Mb of segmental duplications were found per human genome

- Genomes with African ancestry had the highest number (3.97 Mb per individual)

1,247 Complex Structural Variations were identified across all genomes

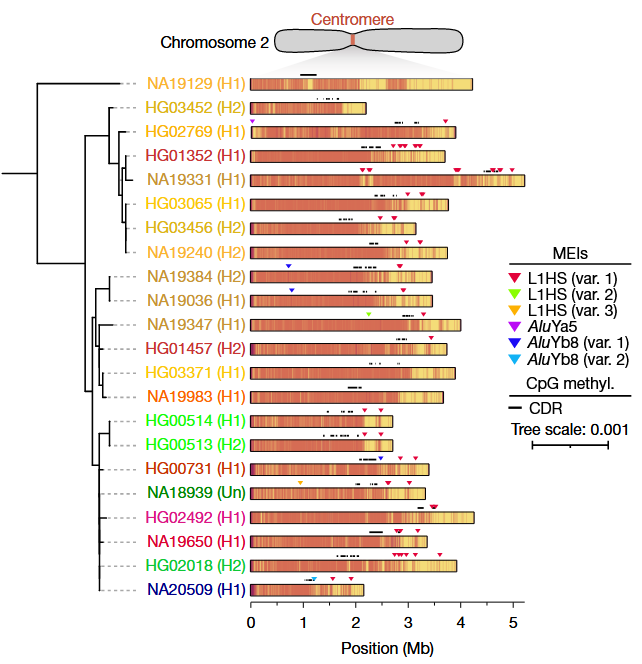

1,246 centromeres were completely and accurately assembled

Genotyping and pangenome

- Pangenome graph was used to genotype variants across 3,202 1kGP individuals using short reads

- Average of 26,115 SVs detected per genome

Genome reconstruction from short reads using this method reached a median k-mer-based quality value (QV) of 45

More rare SVs inferred than previous short-read methods

- 1,490 rare SVs per African individual (compared to 382 previously)

New assemblies increased accuracy to 86.3% (up from ~81%) for medically relevant genes

Conclusions

Successfully sequenced 65 diverse human genomes, producing 130 highly contiguous haplotype-resolved assemblies

Reducing remaining gaps in human genome references by 92%

- Assemblies provided complete sequence continuity for highly complex loci like MHC, and fully resolved 1,246 human centromeres

Centromeric analysis revealed

- Substantial variation in \(\alpha\)-satellite length (up to 30-fold variation)

- Documented mobile element insertions into these regions

Integrating these assemblies into a pangenome reference significantly increased genotyping accuracy when using short-read data only

Detection of a substantially higher number of SVs per individual (26,115 SVs on average)

Transcriptomics for Precision and Personalized Medicine

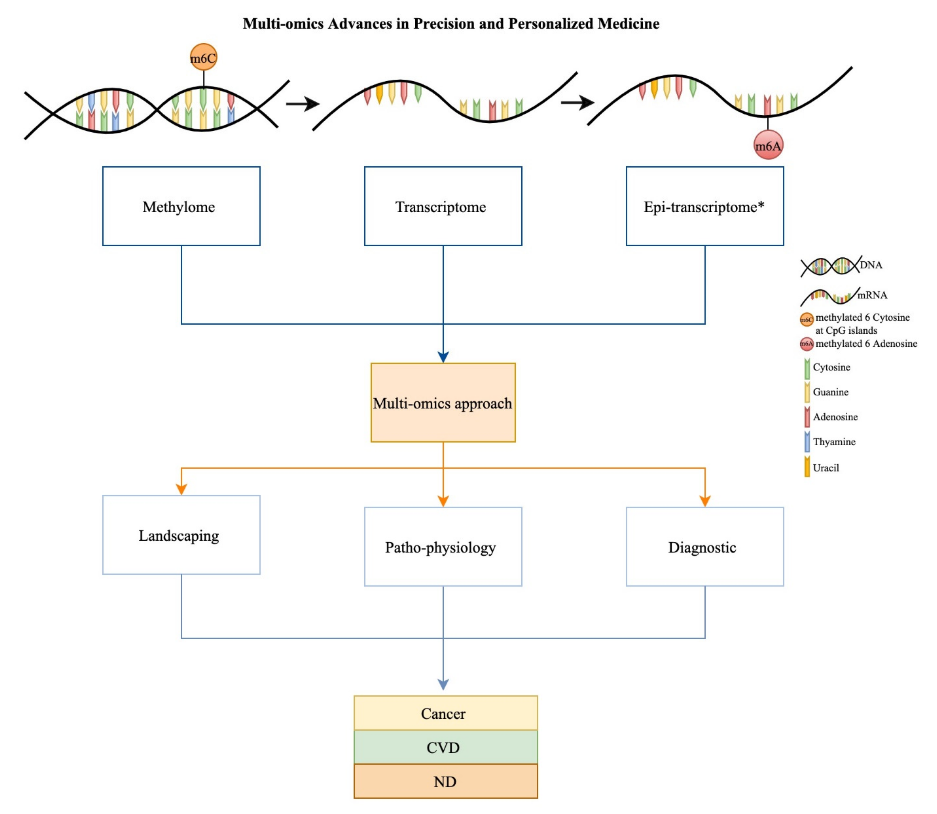

Mubarak and Zahir (2022) reviews recent recent transcriptomics contributions toward personalized and precision medicine.

Background required to understand the paper

- Transcriptomics is the study of all RNA molecules in a sample

- mRNA, which codes for protein

- rRNA, which codes for ribosomes

- tRNA, is used in protein synthesis

- Other non-coding RNAs like lncRNA and miRNA

~70–80% of the human genome is transcribed, but only about 2% is protein-coding

Epitranscriptomics refers to the study of post-transcriptional chemical modifications (e.g. methylation) of RNA

Precision vs. Personalized Medicine

- Precision medicine seeks to pinpoint the precise cause of a disease

- Personalized medicine seeks to identify the cause of the disease within individual contex (e.g. genomic background, health metrics, environment)

What fundamental questions does the paper address?

Review paper: synthesizes many studies to form general conclusions

What are the impacts of transcriptomics and epitranscriptomics on personalized and precision medicine efforts?

- What are the major efforts concerning transcriptomics/epitranscriptomics in key disease areas:

- Cancer

- Cardiovascular disease (CVD)

- Neurodevelopmental disorders (ND)

How are advances being made in both basic research into disease pathophysiology and diagnostics?

How does the specialized area of epitranscriptomics contribute to the understanding and study of neurodevelopmental disorders?

Study design

This is a review article. It does not report on an original research study design but rather synthesizes findings from existing research:

Summarizes and overviews major transcriptomics and epitranscriptomics efforts

Focuses on major advances in transcriptomics for three diseases: cancer, CVD, and ND

The recently emerging field of epitranscriptomics is discussed

- Focusing in depth on its contributions to neurodevelopmental disease

Sample collection

As a review, the authors did not perform sample collection; however, the paper details various sample types and methodologies employed by the studies being reviewed:

- Typical preparation involves

- Isolating total RNA

- Depletion of ribosomal RNA

- Sometimes mRNA is pulled down via its poly-A tail prior to sequencing

- Sample Types in Reviewed Studies

- Single-cells

- Tissue-level samples (e.g. cardiac, brain, blood, saliva)

- Spatial transcriptomics for cancer diagnostics and tracing tumor evolution

Data analysis

The primary output discussed for both microarray and RNAseq assays is a differential gene expression (DEG) profile. Data analysis in the reviewed fields emphasizes:

Microarray experiments comparing gene expression levels between samples (e.g. two-color arrays) or comparing levels to a normal reference (one-color arrays)

Regulatory RNA characterization, including lncRNA and miRNA

- Analysis methods include

- Transcriptome-wide association studies

- eQTL (expression quantitative trait locus/loci) characterization

- Transcriptomics assays often work best when analyzed in the context of multi-omics

- These serve to validate each other

- Present a more complete picture of genomic activity and biological impact

Conclusions

Significant progress has been made in cancer, CVD, and, to some extent, in ND

Advances are occurring in three areas:

Characterizing normal and diseased tissue states

Developing accurate diagnostic profiles that are both personalized and precise

Investigating the impact of environmental interventions and therapies

- Epitranscriptomics, especially m6A RNA modifications, appears to be especially impactful in ND

- The brain appears particularly susceptible to epitranscriptome signaturing

- Brain epitranscriptome is mechanistically significant for brain plasticity

- Therapeutic inroads have been published for

- Cancer (e.g. precision tumor drug targeting)

- CVD (risk mitigation via lifestyle interventions)

- Precision therapeutics for ND is currently lagging

- As the costs of these screens reduce and databases of transcriptome profiles grow in size and rigor, interpretation of transcriptomics will become easier

- Leading to more advances in diagnostics, prophylaxis, and therapeutics

Specific highlights

Haferlach and Schmidts (2020) reported the use of transcriptomics (among other technologies) for acute myeloid leukemia (AML) diagnosis.

Aghdam et al. (2019) reported on the use of miRNAs in prostate cancer prognosis, diagnosis and perhaps treatment.

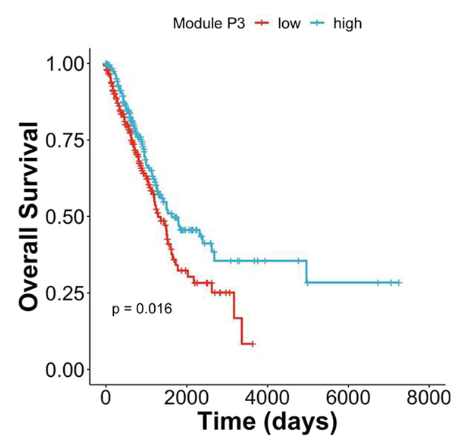

Li et al. (2021) showed strong correlation between lung cancer survival and specfiic long noncoding RNAs (lncRNA).