15 Metagenomics

Acknolegments

NotebookLM, Perplexity and Google were used for collecting and summarizing references while preparing these lecture notes.

What is Metagenomics?

Metagenomics: the analysis of all genomes (microbiome) from all microbiota in a sample

High-throughput sequencing of genetic material recovered directly from environmental samples

Like all high-throughput technologies, metagenomics has revolutionized microbiology

Applications to human medicine (e.g. the human microbiome)

Targeted Approach: 16S rRNA Amplicon Sequencing

16S rRNA amplicon sequencing

Offers quick, cheap sequencing solution to characterize all microbes in a sample (microbiome)

Allows annotation using extremely detailed and well-curated taxonomic databases

DNA is extracted from the environmental sample (e.g. fecal samples)

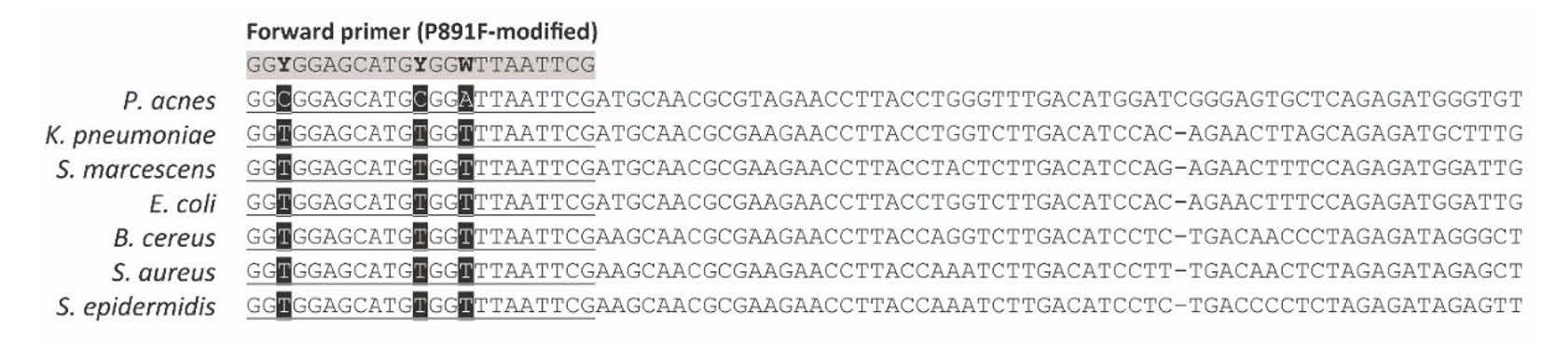

PCR is used to amplify a variable region (e.g. V4-V5) using primers constructed with adaptors and barcodes

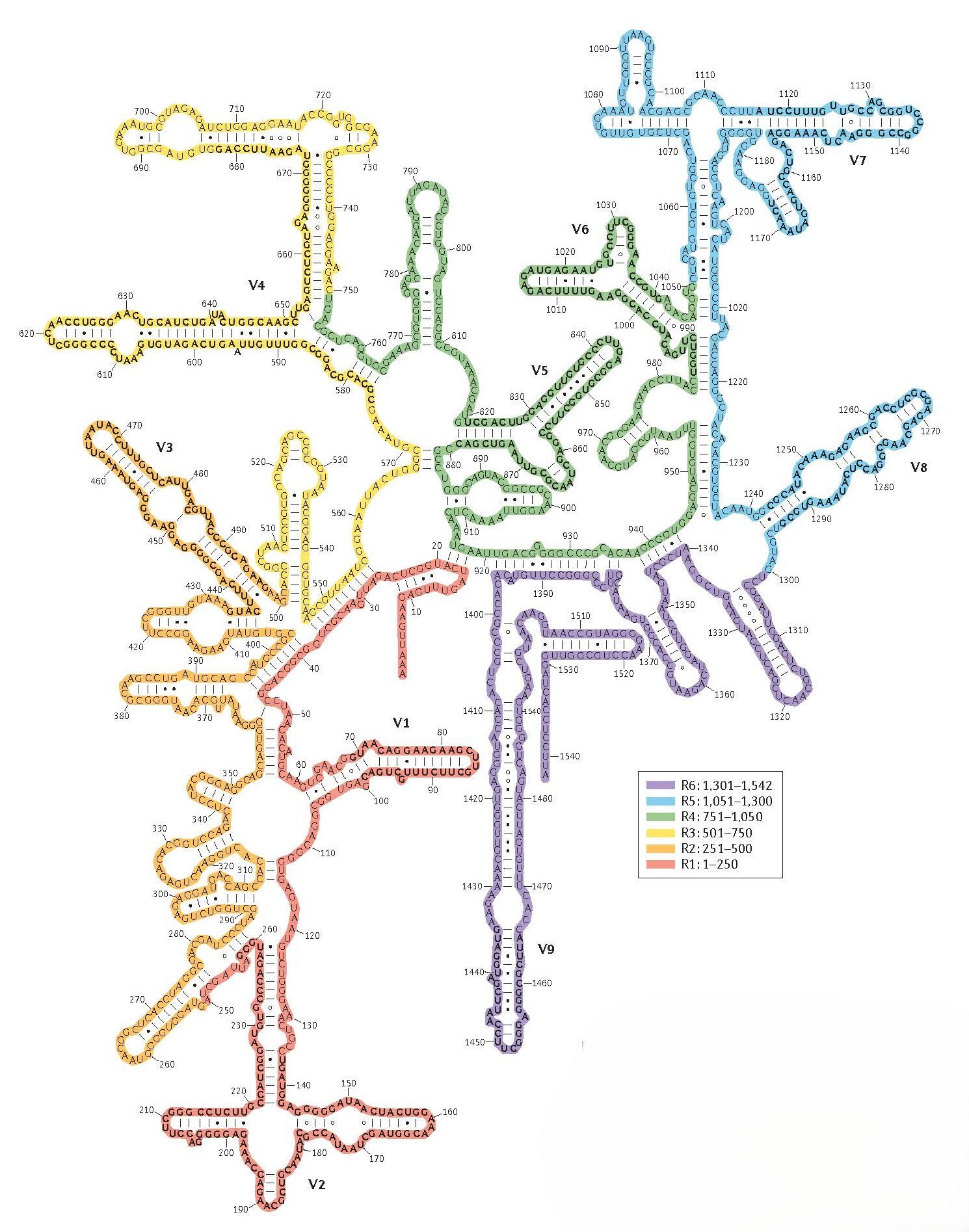

16S rRNA

Entire gene is ~1500 bp long

Many regions are highly conserved across all prokaryotes

Forms the backbone of ribosomes

Encode the structure needed for translation of mRNA to protein

Other regions (V1-V9) are hypervariable and correlate strongly with taxonomy (Gray, Sankoff, and Cedergren 1984; Yang, Wang, and Qian 2016)

- Vary in length from 10 to 100 bp

16S bioinformatic pipeline

Major software platforms used for analysis include

Quality control and alignment

- Raw data undergoes quality trimming to remove low-quality bases

- Pairing of forward and reverse reads into contigs

- Highly conserved regions provide a strong anchor

Removal of artifacts

- Chimeras (biased merged sequences from two origins) are identified and removed, as they artificially increase diversity

- Mitochondrial and chloroplast DNA may be filtered

- DNA from other domains (e.g. human) are filtered

Grouping reads

- Reads are grouped into Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs)

- Typically clustered using a 97% similarity threshold

- Corresponds to the taxonomic threshold between prokaryotic species

Grouping reads

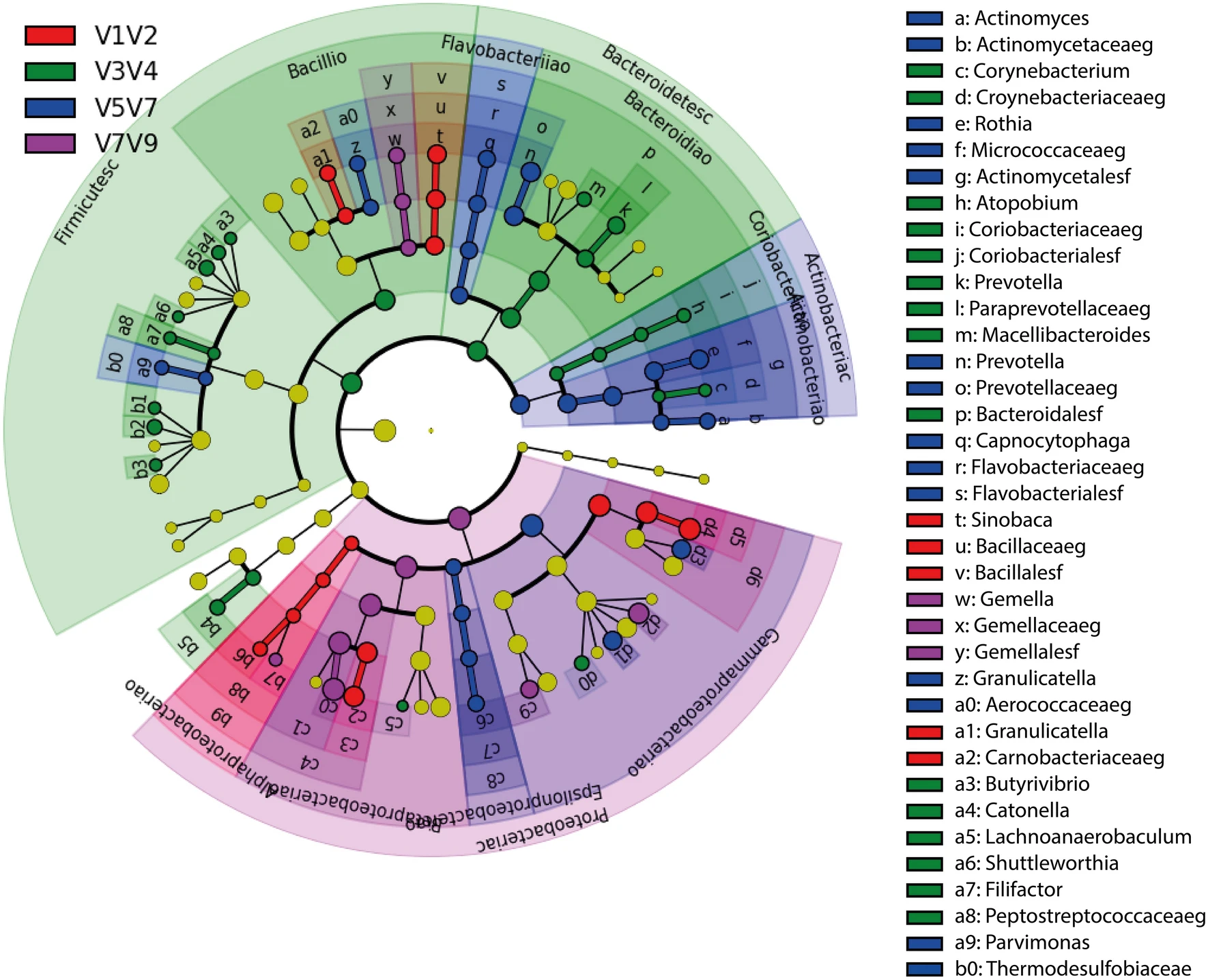

Taxonomic Assignment

- OTUs are aligned against specialized 16S rRNA gene sequence databases for annotation

- SILVA

- Greengenes

- RDP

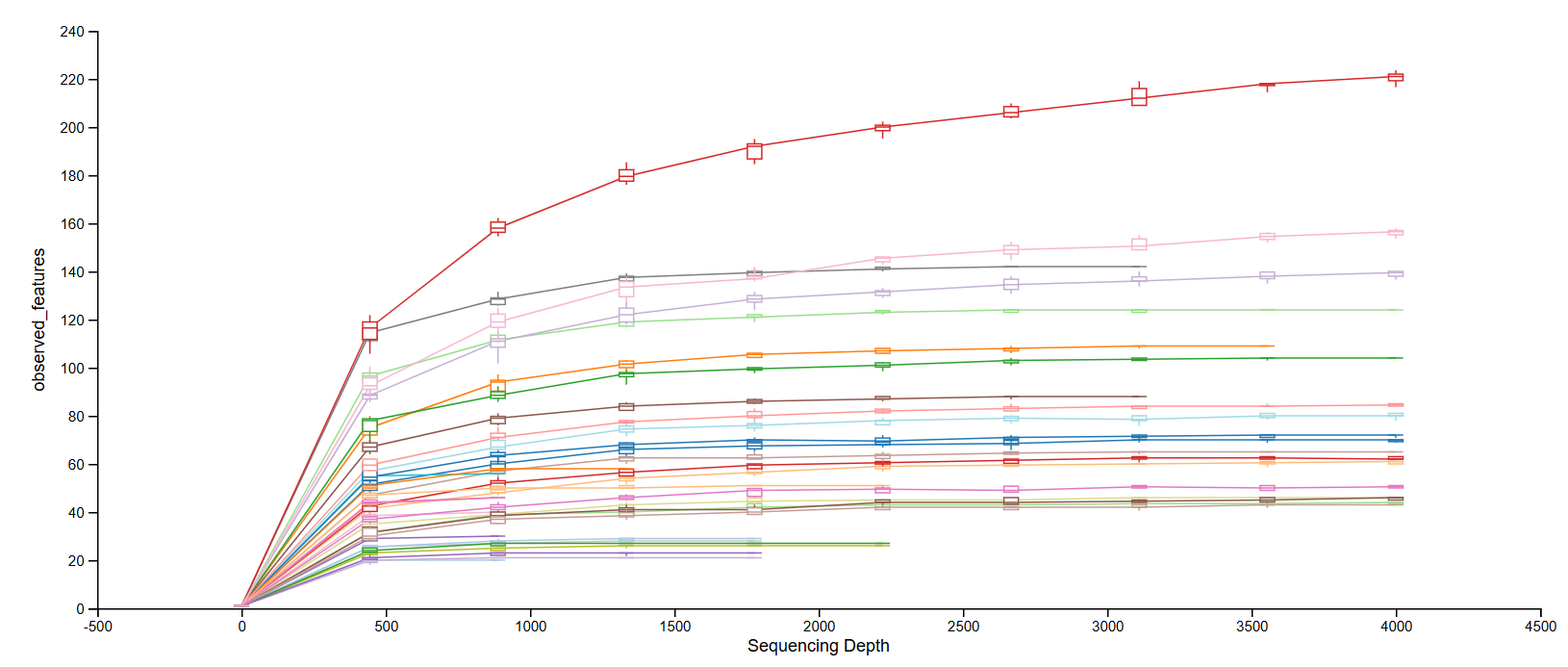

Alpha (α)-Diversity

Measures diversity within a sample group

Rarefaction analysis explores if the sequencing depth was sufficient to capture the true diversity (plateauing curve indicates sufficiency)

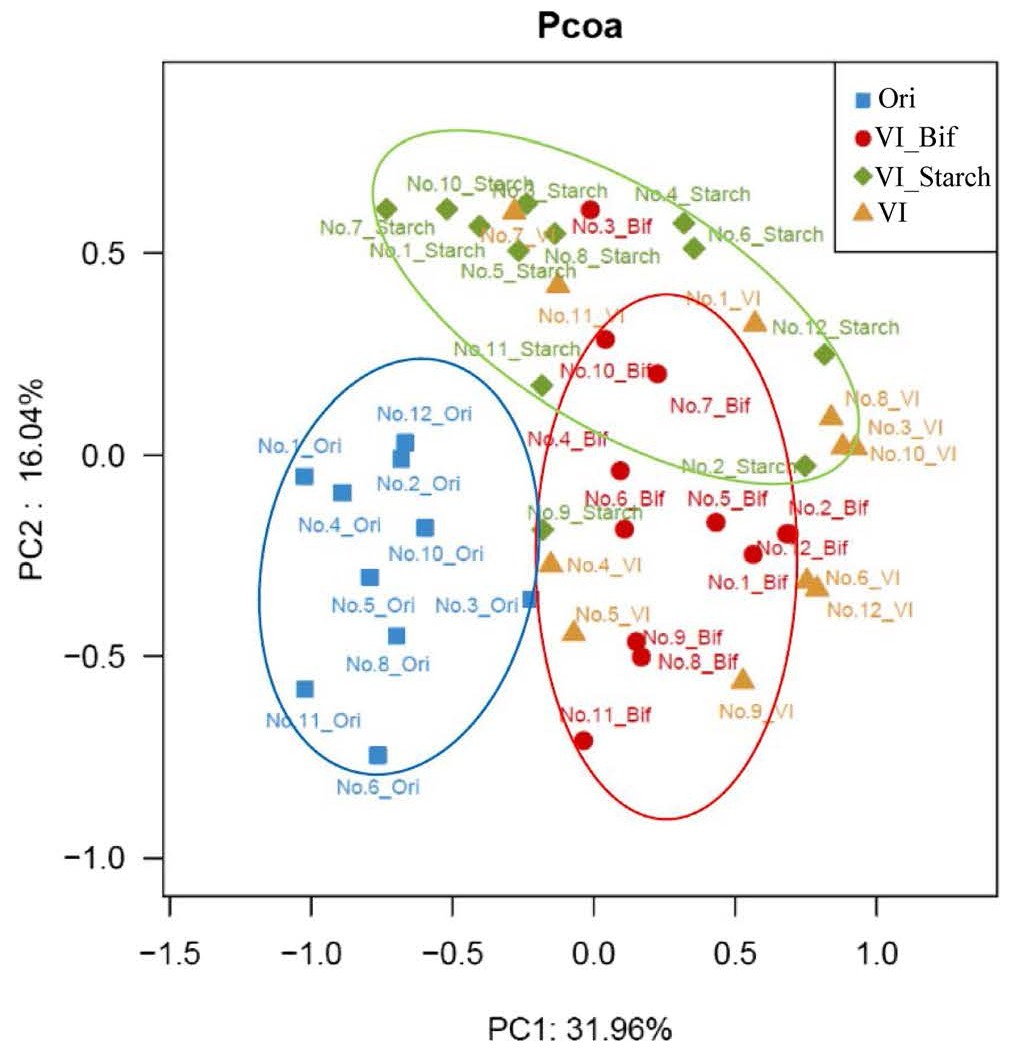

Beta (β)-Diversity

- Measures diversity between groups (similarity/dissimilarity comparison)

- Principal Coordinates Analysis (PCoA) can be used to observe sample clustering and differences

- Dimensionality reduction using dissimilarity matrix as input

- Different from traditional Principal Component Analysis (PCA) that analyzes features directly (e.g. protein abundance)

Comprehensive Approach: Full Shotgun DNA Metagenomics

Full DNA Shotgun Metagenomics sequences all DNA in a sample, aiming to reconstruct genome fragments (Metagenome-Assembled Genomes, MAGs)

Provides functional characteristics and allows investigation of the general diversity of all organisms

DNA extraction should yield at least 50% microbial DNA

Samples are sequenced using high-throughput platforms like Illumina or Nanopore

Pipeline for shotgun data

Preprocessing

Similar to 16S, reads are demultiplexed and subject to quality control

Removal of host DNA by mapping raw reads to the host genome for filtering (e.g. using tools like Bowtie 2)

Assembly

Environmental / microbiome samples are highly complex

Specialized assemblers are used (e.g. metaSPAdes, MEGAHIT)

Assess quality of the assemblies (e.g. CheckM)

Annotation (functional assignment)

Open Reading Frames (ORFs) that encode proteins are predicted

Functional annotation compares predicted proteins to databases like M5nr, SEED Subsystems, or KEGG

Sequence information linked to function, providing the functional potential of the community

Dedicated pipelines/servers

MG-RAST (Metagenomics RAST): User-friendly public resource that automates quality control, annotation, and comparative analysis against multiple databases. It uses BLAST or BLAT for searching.

MEGAN: Links taxonomy with function using the Lowest Common Ancestor (LCA) algorithm, often comparing against NCBI taxonomy

Prediction of function via taxonomy shortcut

- Tools like PICRUSt predict the abundance of gene families in microbial communities based on 16S rRNA marker gene sequences, providing a functional estimate without full shotgun sequencing

Single-Cell Techniques and Advanced Analysis

General similarity to regular scRNA-seq, but also has some unique challenges

No standardized methodologies yet (Ling et al. 2025; Gourlé et al. 2025)

DNA sequencing for single-cell sequencing follows the same principle as sequencing for single genomes

Specialized assemblers (like SPAdes) can handle single-cell genomes/mini-metagenomes

scRNA-seq provides high granularity, allowing full insight into the interplay of transcripts within individual cells

Challenges in scRNA-seq for metagenomics

Sparsity/dropout (similar to regular scRNA-seq)

- Measurements often have large fractions of observed zeros, referred to as “dropout”

- Combination of technical noise and the true biological absence of expression

- Sparsity hinders downstream analysis

Statistical Frameworks

- New statistical frameworks are needed to deal with the high granularity of changes and the uncertainty in clustering/cell type assignment prior to differential analysis

General computational techniques for single cell metagenomics

Data preprocessing and normalization

Necessary for deep-learning models and large datasets like metagenomics

Helps reduce the impact of noise and ensures comparability

Normalization methods include: total count, upper quartile, median, DESeq2 scaling factors, or RPKM/FPKM/TPM which normalize by gene length and reads mapped.

ML / AI: MetaVelvet-DL (Liang and Sakakibara 2021)

- Extension of the MetaVelvet assembler

- Uses deep learning to more accurately identify and partition de Bruijn graphs

- Improves genome assembly and resolution of individual species within complex microbial communities

Exploratory data analysis

- Methods like Principal Component Analysis (PCA), t-SNE, and UMAP are employed for dimension reduction and visualization

- Visualize global gene expression patterns

- Cluster samples with similar profiles

Summary

Metagenomics (16S or shotgun): characterization of entire microbial communities living in specific environments

Example

- Environment: Human skin

- Sample: Skin swabs are taken from the faces of many individuals

- 16S approach: Characterization of microbial diversity on human faces

- Shotgun metagenomics: Characterization microbial diversity and functional / genetic diversity of microbes on human faces

Future Directions

- Whole-genome sequencing (WGS) data is increasingly used for classification and identification

- Single-cell methods are being developed for metagenomics

- Ongoing improvement of sequencing platforms (like Nanopore) and computational tools (like deep learning assemblers) continues to drive the field forward